Playlist

Show Playlist

Hide Playlist

Infective Endocarditis (IE): Pathology

-

Slides InfectiveEndocarditis InfectiousDiseases.pdf

-

Download Lecture Overview

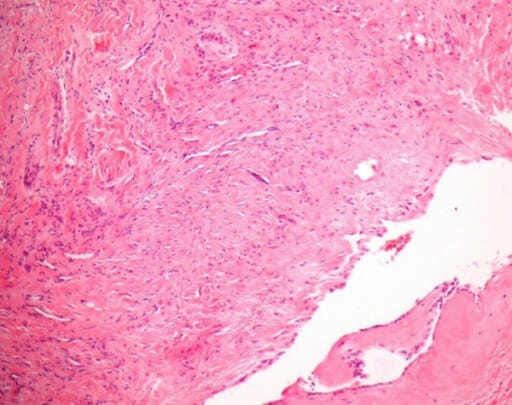

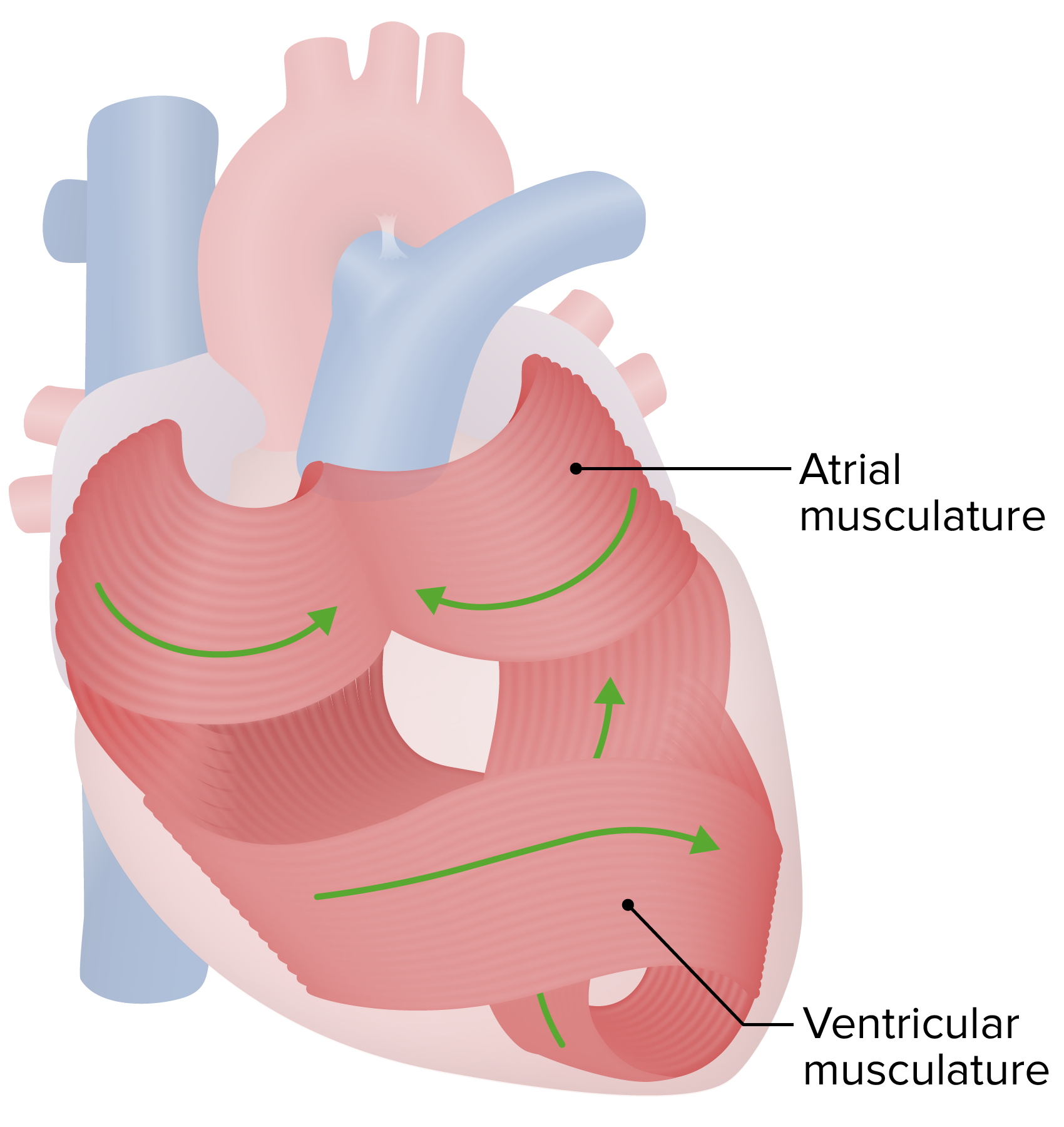

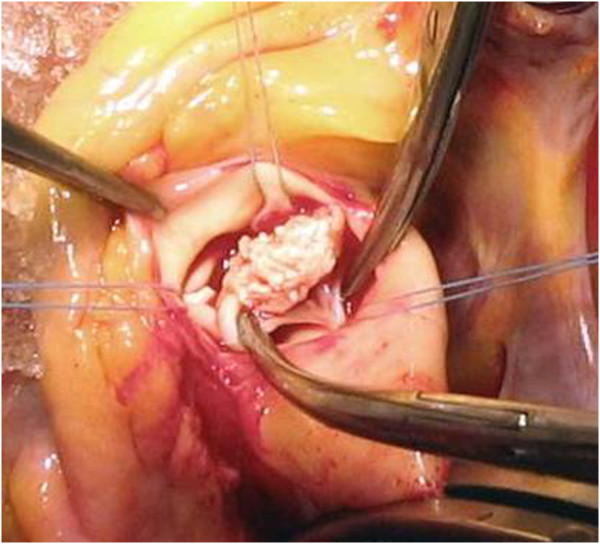

00:01 Well, let’s turn now to the pathogenesis and see if we can enlighten you on how endocarditis develops in the first place. Abnormal valves produce turbulent blood flow. Turbulent blood flow causes the injury of the endothelium. Of course, the endothelium can be further injured by electrodes that are placed in the heart or vascular catheters. Along with intravenous drug use comes the injection of solid particles that are part of what the drugs are adulterated with. Then of course, chronic inflammation from rheumatic heart disease or degenerative valve lesions also produces damaged valves with turbulence. 01:01 So, you've got turbulent blood flow and that is one of the keys to endocarditis. If the endothelium becomes damaged by turbulent blood flow and if there’s a bug that happens to be circulating at the time of the damaged endothelium and if that bug is able to stick, it will likely stick there. So, you have to have circulating bacteria at the same time that you have damaged endothelium. In summary, you’ve got an abnormal valve that leads to a turbulent flow of blood. The turbulent jet of blood damages the endocardium. What does the body try to do? With any damaged surface, platelets are going to adhere to that damaged surface in order to try to heal that damaged surface. Platelets will stick to one another and you get a clump of platelets and fibrin on that damaged endothelium. 02:19 That’s what we call non-bacterial thrombotic endocarditis. There’s a vegetation there on the valve but there’s no bug in it. Now, if you have microbes in the bloodstream at the same time especially those that can adhere to platelets and fibrin, you’ve got yourself infective endocarditis. 02:50 It’s no longer non-bacterial thrombotic endocarditis, it’s bacterial thrombotic endocarditis. 02:59 Here, you can see a large, friable vegetation on the mitral valve. We call a vegetation, all those little excrescences on the mitral or aortic or whatever valve, that’s called a vegetation. Here are some examples of vegetation, one on the aortic valve, a native aortic valve and a prosthetic valve. Let’s then talk about bugs that are loaded for bear and are able easily to cause endocarditis. Foremost among these are the α Strep. Some of the common ones are Strep mutans and Strep sanguinis. 04:00 Actually, there are now several groups of mutans strep. So it’s probably not just a single organism anymore known as Strep mutans. It’s probably the mutans streptococci. Well, many of these organisms produce dextran. Dextran is a complex extracellular polysaccharide that’s produced by some of these strep that cause endocarditis. It allows organisms to adhere to inert surfaces like teeth, for example. 04:41 Of course, if they get into the bloodstream and find damaged endothelium, that non-bacterial thrombotic endocarditis, they can stick there too. Some of these α Strep have Fim A which is a 36kDa protein located at the tips of the organisms right at their fimbriae. 05:07 That mediates attachment to this platelet-fibrin matrix. So, you can see that those organisms are well-suited to stick to non-bacterial thrombotic endocarditis. Streptococcus bovis is notorious because when you have bacteremia or endocarditis due to that organism, just doctor to doctor, you should ask yourself the question, does the patient have colon cancer? If I had a patient who had Strep bovis infective endocarditis or even bacteremia, I would probably schedule that patient for a colonoscopy. That’s the association. It’s not all that common but you would feel horrible if you missed it. So, how do you get all the bugs in the bloodstream? Well, that would be from trauma or damage to a mucosal surface that’s heavily colonized by those bugs. The classic would be the oropharynx and nasopharynx loaded with those α Streptococci, so is the GI tract. 06:23 The GU tract is not loaded with those bugs. But as men age and develop benign prostatic hypertrophy, they are prone to getting infections not only due to things like E. coli but due to the enterococcus. 06:44 The enterococcus probably causes about 10% of urinary tract infections and maybe a little more in men with prostate problems. So, if those men were to get instrumented, so say have a partial prostatectomy and they had enterococcus in the urine at that time, enterococcus is one of the worst organisms to cause endocarditis. That’s because it’s very difficult to treat. It certainly is a common player in this process. 07:22 The number of bacteria per mL that get in the blood depends upon the trauma of the procedure and the number of the organisms on the surface. One thing has been recently discovered in the last 15 years is that the risk of getting bugs in the bloodstream just from your daily activities is far greater than that from most dental procedures. For example, if you were to have your teeth cleaned, you would very likely get bugs in the bloodstream. Most people do when they get their teeth cleaned. 08:13 If you were to have a dental extraction, almost everybody gets bacteria in the bloodstream from just getting a tooth pulled. Well, that takes about 30 minutes then the bacteremia goes away but what about the daily activities such as brushing your teeth, flossing your teeth? Each of those activities carries with it at least a small to moderate risk of bugs in the bloodstream. We’re doing that at least once and twice and maybe more than that in some individuals. So, we’re doing that on a daily basis. 09:00 So, I think you can see that just the daily activities have a lot more opportunities for bugs to get into the bloodstream. When those data were recognized in studies, that led to the changing of the recommendations about giving antibiotics. We were finding out that the risk of daily activities was actually thousands of times greater than a 30-minute episode following a dental procedure. 09:36 Those guidelines were changed in an article published in Circulation in 2007.

About the Lecture

The lecture Infective Endocarditis (IE): Pathology by John Fisher, MD is from the course Cardiovascular Infections.

Included Quiz Questions

Blood cultures from a man with infective endocarditis grow Streptococcus bovis. A workup for which of the following conditions is most likely indicated?

- Colon cancer

- Lung abscess

- Diabetes

- Urinary tract infection

- Dental abscess

Which of the following is present in all cases of infective endocarditis, regardless of the etiology?

- Cardiac endothelial damage

- Valvular prolapse

- Congenital heart defect

- A history of intravascular catheterization

- Degenerative valvular disease

What property of the viridans streptococci most significantly affects its adherence in the pathogenesis of endocarditis?

- Dextran

- Cillia

- Intracellular proteins

- Vacuole excretions

- Cell membrane phospholipids

What is non-bacterial thrombotic endocarditis mainly composed of?

- Fibrin and platelet matrices

- White blood cells and bacteria

- Antigen-antibody complexes

- Red blood cells and myocytes

- Cholesterol plaques

Customer reviews

5,0 of 5 stars

| 5 Stars |

|

1 |

| 4 Stars |

|

0 |

| 3 Stars |

|

0 |

| 2 Stars |

|

0 |

| 1 Star |

|

0 |

Its a really nice summary of what do any doctor needs to know to be prepare in the mission of infront the pathology